In my two previous posts concerning Christian Politics, I maintained that Judeo-Christian citizens of the United States must be involved in the politics of this nation. Accordingly, the major question for me is not whether we should be involved in all stages of the political process, but precisely how shall we be involved?

Some of the material in this post came from Facebook conversations that took place over several days after my second post in this series appeared. I chose to use pertinent material from these on-line conversations for part of this present post because not all people who read my posts on MikeFrosolono.com access or participate in Facebook discussions.

Adherence to the Constitution?

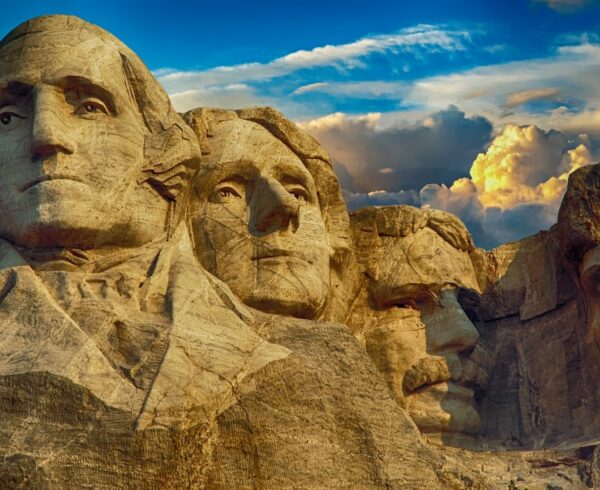

A constant theme that many people express comes from the idea that the United States, explicitly or implicitly, is a Judeo-Christian nation. This proposition “logically” leads to Judeo-Christians having special religious and political privileges under the US Constitution (along with the Declaration of Independence, the country’s two most notable secular documents). Proponents of this view read more into the historical record and the Constitution than I and many Constitutional scholars do. (Yes, I am aware that some Constitutional scholars disagree with this position.) Alleging the United States is a Judeo-Christian nation by definition detracts from valid points regarding Judeo-Christian involvement in the politics of our democratic republic.

I am neither a Constitutional scholar nor am I exhaustively familiar with the Federalist Papers and other parts of the written documentation the Framers produced when crafting the US Constitution. Nevertheless, I believe I am correct on these points: (1) The Framers did not mean that Judeo-Christians should be excluded from participating in the politics of our nation and in the federal government; (2) The Framers did not award political supremacy to Judeo-Christians; and, even more importantly, (3) The Framers did not want a governmentally-supported church, much less a legal theocracy.

To impart any meaning other than the plain words of the Constitution requires a person to be a loose Constitutional constructivist. While I sometimes have difficulty with the concept, I resonate with the position of a close Constitutional constructivist or originalist like the late Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) Justice Antonin Scalia: Rely upon the plain words of the Constitution and meanings those words had for the Framers. In this context, we must remember that the primary Founders and Framers were Deists who did not accept the divinity of Jesus Christ, the validity of miracles, and numerous other precepts of traditional Judeo-Christianity. As a side note, of the many people I have engaged in discussions on these issues and who accept the principle of Judeo-Christian legal supremacy, none have accepted the idea that SCOTUS should make any ruling except as grounded on the plain words of the Constitution. That is, SCOTUS should refrain from interpreting the law on any basis but the plain words of the document in order to avoid the pitfall of “making laws.” Yes, I admit my sample size is too low for statistical veracity.

I believe Judeo-Christians are obligated to participate in the politics and government of this country; but, I fervently object to converting the United States into a legal theocracy. Such attempts leave me wondering: If we were to establish a legal Judeo-Christian theocracy, which of the several denominations would be the primary determinate of the rules? I cannot think of a single denomination that I would want to set the rules for a theocracy. I wouldn’t want my denomination, United Methodist, to be the “prime mover” in such a government.

Missing the Crux

Discussions about Constitutional privilege—explicitly or implicitly—most often miss the central question regarding Judeo-Christian participation in politics: Will Judeo-Christians, regardless of the type of government under which they exist, perform their duty as the Gospel teaches? Carrying out this duty is easier under a democratic republic than under a tyrannical form of government, especially one overtly antagonistic to Judeo-Christians. The historical record, however, demonstrates that Judeo-Christians can successfully perform their duty even in the face of lethal government hostility. To illustrate this point, I often bring up the success of Judeo-Christians in the Roman Empire.

In the first three centuries after Christ’s resurrection, Roman laws encouraged the torture and killing of Christians. That is, Christians had no legal protection in the Roman Empire until the Emperor Constantine promulgated the 313 AD Edict of Milan that formally declared Christianity a legally permitted religion in the empire. Nevertheless, the number of Christians rose from approximately 1,000 (0.0017% of the population in the Roman Empire) in 40 AD to nearly 34 million (56.5%) in 350 AD. This history of Judeo-Christians within the Roman Empire shows why changes in hearts and minds through profession, proclamation, witnessing to, and rejoicing in the risen Christ, and serving our brothers and sisters are highly effective tactics. Legislation sometimes can change behavior but seldom, if ever, changes hearts and minds.

The Best Legislative Approach

I believe the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses within the First Amendment to the Constitution provide all the legal authority for Judeo-Christians to perform their Gospel duties in the United States:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . .

These clauses define a level playing field for all religions, including the various manifestation of Judeo-Christianity, within our democratic republic. Judeo-Christians should assiduously use the political system of the United States to preserve this level playing field. Seeking a legislative advantage, rather than equal opportunity, for Judeo-Christianity to compete in the religious marketplace smacks of weakness and lack of confidence.

Some people mistakenly interpret these clauses to mean the Constitution imposes an impenetrable “wall of separation” between our churches and religious activities on one side and government on the other. Thomas Jefferson, in his 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, wrote what arguably is the most famous statement about this wall:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his god, [the people, in the 1st Amendment,] declared that their legislature should make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, thus building a wall of separation between church and state.

Simply put, this wall of separation does not prohibit Judeo-Christians from engaging in political activity or even working for federal or state governments. The wall of separation means implementation and preservation of the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses. If for no other reason than self-preservation, Judeo-Christians should work for this implementation and preservation: If current demographic changes persist, one day Judeo-Christians may not be in the majority within the United States; therefore, the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses will become even more critically important to Judeo-Christians.