I participate in the Köehler Author Forum on Facebook, which is limited to participants who are authors with Köehler Books. A recent topic on this forum focuses on why the participants became authors and what defines a person who claims to be a writer.

My writing life began in the early evening of a weekday when I was in the second grade, probably in the spring, in LaGrange, GA. Mother, Daddy, and I had returned that fall from Chickasaw, AL, where Daddy helped build Liberty cargo ships in a WWII shipyard in the Mobile area. In LaGrange, my parents and I lived with my paternal grandparents, Daddy Mike and Mama Ruth Frosolono, in what at the time seemed like a large house. Daddy resumed working in the family tailor shop, mother found a job as a beautician. I happily attended Harwell Ave. Elementary School.

When my father came home from work that spring evening, he asked me, “What did you do today, Michael?”

“After school I went home with Billy so we could play together.” At this time in LaGrange, children were not as “protected” as they are now. Billy and I walking from the school to his home about a mile away and across some busy streets would not have been viewed with alarm. The further we walked from the school, which was about a half mile from Daddy Mike and Mama Ruth’s home, the houses became bigger and finer. New cars were parked at some of the homes. Billy’s mother welcomed us with a snack and sat us in front of the TV, something I had not previously seen. She tuned the TV to a children’s program, which did not impress me. I asked Billy if other programs were on the TV. I remember him going through the three or four available channels until he found a program I liked. After that program ended, Billy showed me through his large home. I still remember how grand the furniture was and the fact that Billy had his own room. I slept in Daddy Mike’s bedroom. Billy’s mother drove me home in their fine car.

I related the afternoon events to Daddy and asked, “Why don’t we live in big house with a TV? Why don’t we have a new car?”

“Michael,” Daddy said, “Billy’s family is rich.”

At that time, I lived a very insular life bounded by home, school, the First Presbyterian Church, and the tailor shop. This insularity probably explains my follow up question, “But, aren’t we rich?”

Daddy’s face hardened and his voice sounded almost angry. “Michael, we’re not rich, we’re poor. We’ll always be poor, and you had better learn that you’ll always be poor, too.”

I didn’t like the answer but I had already learned not to argue with Daddy under such circumstances. Daddy left me in the kitchen with the family maid, Mattie. She hugged me before we set the table for supper.

I told Mattie, “I won’t be poor, I won’t let that happen.”

She sighed. “Then, child, you have a long road ahead of you.”

These two conversations opened my eyes and I lost some of my Frosolono family insularity; but, that’s a story for another blog post. I became an early and voracious reader, preferring the life opened to me in books rather my life within the family. Somehow I realized that I shouldn’t discuss with my family, especially Daddy, what I was learning from my reading and my resolve not to be poor. In a sense, I lived a double life.

As time progressed, I began evaluating careers that might keep me from being poor when I grew up. Important to this story is the fact that this evaluation began before I finished sixth grade. I liked playing baseball and football but I realized sports would not be my way out of poverty. The more I read, the more convinced I became that I could write books.

Miss Harden, my eighth grade science teacher at Hillside Jr. High opened my mind to the wonders of science. This enchantment became solidified through science classes I took at LaGrange High School. I well remember the day in my junior year when I talked after school with Mrs. Raymond Smith, who taught my sophomore English and senior Chemistry classes. I told Mrs. Smith that I was having a hard time deciding whether to be a writer or a scientist.

She smiled before answering. “You can be either one; however, you might want to be a scientist first. You need sufficient life experiences in order to have something to write about. You have a talent for science.” She paused. “As I told you on your first day in my English class, learning to write well will be of inordinate value in whatever career you choose.”

That evening, I found the courage to announce at the supper table, “I need to go to college.” I knew Daddy would be opposed to this idea. He had been insistent that I should learn a trade, preferably in the tailor shop, in order to make a living. I began working in the tailor shop while still in elementary school and continued through high school. I sometimes worked in the shop during college.

“Our kind doesn’t go to college, that’s for rich people,” Daddy pronounced.

“Well, I’m still going to college.”

“You’ll have to pay your own way because we can’t afford to send you to college. You need to stay here at home and help me run the tailor shop.”

The way I managed to pay my way through LaGrange College, with modest financial help from Daddy—including free room and board in our home—is also another story for another blog post. I graduated with a full double major in Biology and Chemistry. Andrea and I married one week after graduation and we left Georgia for graduate school at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. After receiving my Ph.D. in Biochemistry, Andrea and I pursued the life of an academic family for 20 years.

Mrs. Smith was correct: My ability to write well helped me make my scientific “bones,” especially through some of my published, peer-review articles. I came to enjoy writing grant applications, and was so successful that I became known in some circles as “Dr. Grant Getter.” In fact, I enjoyed experiment planning, data evaluation, and writing aspects—grant applications, reports to the National Institutes of Health, publications—much more than I liked the actual bench work. Fortunately, I had great people working with me to perform the bench work.

After 20 years, Andrea and I became disenchanted with academic life. I was “seduced” to join the Clinical Research Department in the old Burroughs-Wellcome Pharmaceutical Co. near Chapel Hill. Once again, the writing aspects of the work consumed much of my time as I prepared feasibility reports, Investigational New Drug Applications, study protocols, final medical reports, and New Drug Applications to name some of the writing activities. I like to think I helped several of the people with whom I collaborated become better writers. Both in academia and the pharmaceutical industry, I tried to impress upon my co-workers that great results don’t amount to much unless the story of those results can be presented in a readable and understandable fashion.

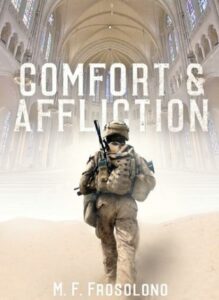

The familiar discontent once more reared its head after 20 years. Andrea and I left the pharmaceutical industry for Lavonia, her hometown in northeast Georgia. I think my increasing discontent in large part resulted from my desire to begin writing novels. We stayed in Lavonia for 12 years. I allowed myself to become enmeshed in country politics but I still managed to complete my first novel—Beyond Duty—and an edited collection—Thoroughly Biased Opinions—of the columns I wrote over the course of nine years for the Franklin County Citizen weekly newspaper. We moved to Austin, TX, where I wrote my second novel, Comfort and Affliction, which Köehler Books will publish on April 1, 2015.

So, the above is long summary of my writing endeavors and credentials. Do I consider myself a good writer? Not really but I try, a concept that brings me back to the Köehler forum. What does it take for us to be writers? First and foremost, spend most —or at least a lot —of our time writing to produce completed products worthy of publication in various forums. Yes, I consider people to be writers if their main products are well-written blogs and self-published books. Of course, getting paid for our products amounts to a great validation of our writing abilities.

I enjoy my writing life, even on those days when I turn out only 500 words or less. Sometimes I’ve been satisfied with one great sentence.

I don’t see any need on this post to emphasize the discipline required for most people to become writers: That concept is embedded in the requirements for the writing life. We can’t be writers if we only talk about being writers: We must write in order to be writers.